Tuttle and Thoreau correspondence concerning “Wheeler’s Lot” 1854

Question: What is Tuttle describing to Thoreau and asking Thoreau concerning Wheeler’s Lot?

Answer: Tuttle is describing two different procedures he had used to measure the area of Wheeler’s lot and asking Thoreau’s opinion as well as Thoreau’s experience concerning a related issue of compass correction for magnetic variation in Concord.

Area measurement of a land parcel area was a common statistic provided by Thoreau for most of the lots that he surveyed from 1837-1860. Many of the land parcels were described as “woodlots”. An area measurement was used to calculate the amount firewood or building lumber and therefore dollar value that could be expected from a woodlot prior to its being cut.

According to a Surveyor’s Manual that was in Thoreau’s library (Davies, Charles “Elements of Surveying and Navigation”, 1846):See:

http://play.google.com/books/reader?id=KpVHAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP5

There were two commonly used methods for computing land areas, given a map of known scale.

“1. Divide the existing map of land lots into geometric units (e.g. squares and triangles) and then compute the area of each of each and sum their total area.

2. From an existing map or field notes of the bearings and distances for each lot originally recorded with compass and chain, compute the area of each lot summing their total area.

(Both procedures were alluded to by Tuttle in his letter to Thoreau)

When using compass and chain there are two sources of error:

1st. Inaccuracy of the surveyor’s field observations when recording of distance or angle.

2nd,. Local attractions or the derangement which a compass needle experiences when brought into the vicinity of iron-ore beds, or any ferruginous substances.

To guard against these sources of error, reverse bearing should be taken at every station: if this and the forward bearing are of the same value, the work is probably right; but if they differ considerably, they should both be taken again.

Differences between measurements taken in each direction also may be used to estimate “balancing” corrections.

THE TRAVERSE TABLE AND ITS USES

These tables which are included in the Davies book, show the latitude (N-S) and departure (E-W) corresponding to bearings for each survey line segment expressed in degrees and quarters of a degree from 0 to 90°, and for every course from 1 to 100, computed to two decimal places.

By use of these tables the latitude (angle) and departure (distance) of a course segment may be computed to any desired degree of accuracy.

Davies notes that given a surveyor’s field measurements describing the straight line segments defining the perimeter of a property boundary, it is possible to compute the area of the property in question and also create a graphic plot of its perimeter.

Tuttle’s Letter follows (with my comments in italics):

Made a very small plan of it about 2 rods (i.e. 33 feet) to an inch (scale)

An enlarged copy of a map can be made by use of a pantograph, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantograph

Thoreau owned such a device currently on display in the Concord museum and shown on their website.

http://www.concordmuseum.org/henry-david-thoreau-collection.php

Within the Concord Museum Collection, go to: Catalog #: TH0012E, Object Name: Compass

I should judge & cast it up making 14 A 22 rods

(i.e. I manually drew an enlarged plot and divided it into geometric units (e.g. squares and triangles)then summed the area of each lot, resulting in an estimate of 14A 22 rods,.)

The plan was so small (& so unskillfully drawn) that I told Mr. W that very little reliance could be placed upon it in computing areas.

(I next computed the area using the compass and chain technique described by Davies.)

Since then I have computed the area several times by the aid of traverse tables

Finding the Lat & Dep both in chains & decimals of a chain & in rods & dec of a rod & obtaining answers

the bearing of the 3d course N 57 E & taking out the Lat & Dep in rods & decimals of a rod I made

the area to be 13a 109,57r. (resulting in an estimate of 13A 109.57 rods,.)

I find but little (,01 of a rod) diff between the Eastings & Westings & but ,19 of a rod between the

Northings & Southings. & in balancing the survey I subtracted the Diff between the North & Southings

from the Southing of the 7th course.

Will you have the kindness to inform me by what method you computed the Lat in question:

if by plotting to what scale your plan was drawn,

or if by the traverse table whether you took out the distances in chains or rods & to how many decimal places you found the Lat & Dep. of each course.

What is your general method of computing areas?

(i.e. Do you generally use the geometric units or the Compass and chain measurements?

We know from an review of Thoreau’s Land Surveys that he used both techniques beginning with geometric units and moving on to compass and chain once he had acquired a survey compass.

& What is the present variation of the needle in Concord?

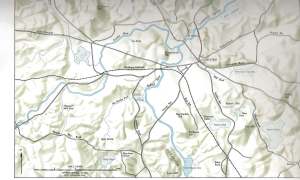

The question concerning “the present variation of the needle in Concord” refers to difference between True North and Magnetic North that Thoreau typically included on the plots he made of his Concord area surveys, the procedure for which Thoreau described in detail in his Field Notes of Land Surveys on Feb 7, 1851 on page 38.

For example Thoreau reported a Variation = 10’1/8W on his map of Oct. 3, 1853.

Terminology references:

Traverse table operations: see p. 105 of Charles Davies “Elements of Surveying”

Departure ibid. p. 105

Balancing the survey see p. 109 of Davies

THE TRAVERSE TABLE AND ITS USES. ibid. p 19. This table shows the latitude and departure corresponding to bearings that are expressed in degrees and quarters of a degree from 0 to 90°, and for every course from 1 to 100, computed to two places of decimals. The following is the method of deducing the formulas for computing a traverse table; by means of these formulas and a table of natural sines, the latitude and departure of a course may be computed to any desirable degree of accuracy. P.105

Traverse (surveying)

Traverse is a method in the field of surveying to establish control networks. It is also

used in geodetic work. Traverse networks involved placing the survey stations along a

line or path of travel, and then using the previously surveyed points as a base for

observing the next point. Traverse networks have many advantages of other systems,

including:

1. Less reconnaissance and organization needed.

2. While in other systems, which may require the survey to be performed along a

rigid polygon shape, the traverse can change to any shape and thus can

accommodate a great deal of different terrains.

3. Only a few observations need to be taken at each station, whereas in other survey

networks a great deal of angular and linear observations need to be made and considered.

4. Traverse networks are free of the strength of figure considerations that happen in triangular systems.

5. Scale error does not add up as the traverse is performed.

Click to access traverse.pdf

Fletcher’s question to Thoreau concerning methods for computing areas is indeed interesting, and two different methods for dong so are described in Davie’s book.

Balancing the survey’s 7th course to which he refers likely reflects the fact that the 7th course is also the longest at 12.81 chains of the 9 courses and potentially subject to variation over its length compared to other shorter courses.

Although both Thoreau and Wheeler arrive at approximately the same area measurement value i.e. 13.7 A and 13.5 A respectively, Davies procedure for area measurement suggests a more precise value to be 13.45 A.

Wheeler’s first measurement by casting up or enlarging a small map and then summing a grid overlay resulted in a value of 14A+22R. = 14.13A

Wheeler’s second measurement applying Davies’ procedures produced 13A+109.57R=13.68A

Thoreau’s measurement of 13+112R = 13.70 may have been derived from the work done by Wheeler, we will never know but Thoreau and Wheeler reported the same value and both are different from Davies’ presumed correct value by an identical amount.

The reason for the approximately 2% difference I suspect is due to the time required to carry out Davies procedures manually with pencil, paper, traverse tables and logarithms rather than computers and spreadsheets.

Although additional precision was possible the 98% accuracy level was adequate.

If Thoreau ever responded to Wheeler we do not have a copy.

Thoreau may have accepted Wheeler’s measurements and included them in his Field Notes of Surveys.

T said 13A + 112R = 13.7A, a difference of only +2R more than Wheeler but +40R over Davies

13.7A-13.45A=.25A .25/13.45=.018 =+1.8% T greater than D

W said 13A + 110R = 13.68A

D said 13A +72R = 13.45A

Note: R = 1 square rod, 160 R = 1 A

Tuttle December 22, 1854

-6.66Letter from William Davis Tuttle to Thoreau dated December 22, 1854

Area of Wheeler Lot initially measured by Tuttle on an enlargement by plotting produced 14 A. 22R.

Area of Wheeler’s Lot subsequently measured by Tuttle using traverse table produced smallest value of 13A 11.9 R plus other values up to 13A 106.5 R.

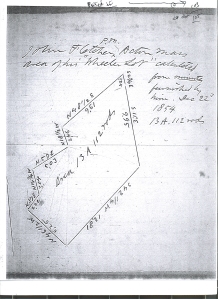

Thoreau calculated the area of John Fletcher’s of Acton,” Wheeler Lot” from minutes furnished by Fletcher, Dec. 22, 1854 and who estimated the area to be 13A 112 R.

Tuttle’s initial estimate by plotting = 14A 22R.

Tuttle’s several estimates by traverse table range from 13A 11.9R to 13A 109.57R.

Thoreau’s estimate calculated from minutes = 13A 112R. (largest of Traverse estimates)

Davies’ traverse table procedure says area correct value = 13A 72R. See: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/pub?key=0AroG1WG-7zJ-dDN2emNRWGF0UDdJQk9WeUZLQkM4bEE&output=html

Thoreau’s area estimate is 1.8% or a quarter acre greater than Davies’.

Note that resulting Thoreau’s estimate of 13A 112R is within 98.2% of Davies rules as described by him and incorporated in an Excel spreadsheet above.

The data Thoreau used from Davies Tables are only given to two decimal places.

Thoreau could not assume greater precision in his result than in his data and if he were to compute all of the values required by Davies Rules it would be time consuming process involving pencil, and paper, reference tables, and logarithm tables.

I assume Thoreau had many other interests he pursued and the time required to compute the Area value to an additional decimal that required would not be warranted.

Davies’ tables were only given for quarter angle increments and would not have been applicable to most of Thoreau’s because every survey with exception of the Wheeler Lot shown above that involve a 1/8th degree angle specification by Thoreau in the Bearing specification.

However Thoreau may have computed the values required using the same equations Davies used in preparing the tables.

Measurements with chains were said to be precise to plus or minus one link in 100 (the length of the chain). I.e. 1 %

Credits for the above research project go to Beth Witherell witherell@library.ucsb.edu who suggested and funded the project.